Warren Weaver’s Story

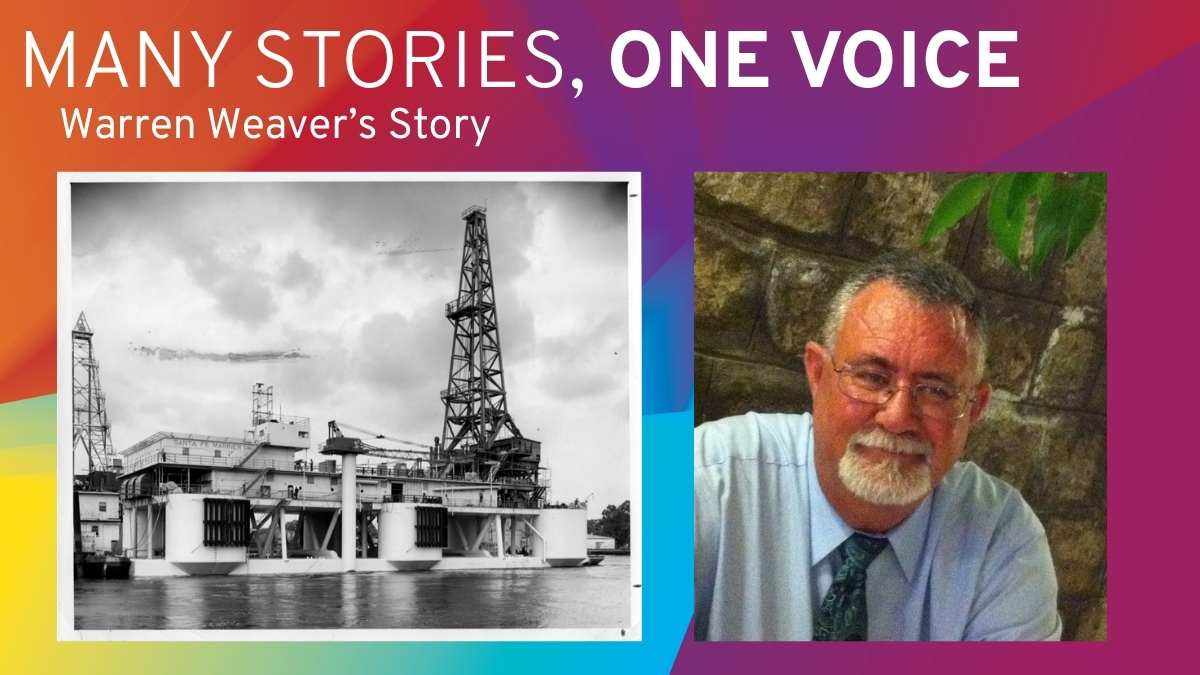

On the left is a photo of the Santa Fe Mariner 1, one of offshore rigs Warren was assigned to. The Santa Fe Mariner 2 - the first rig Warren worked on as a roustabout - had the derrick in the middle.

Warren Weaver – contributed significantly to the Association and its goals during the development of the IMO Code for the Construction and Equipment of Mobile Offshore Drilling Units, 2009

My Introduction to the Oil Patch

My journey into the oil patch began in 1960, when I was just seven years old. My father was a Schlumberger engineer, and from time to time he would take me along on an offshore (inland barge) logging job out of Venice, Louisiana. Sitting beside him in the logging unit, I was allowed to run the winch under his careful instructions — he would tell me when to stop and when to go. I don’t recall exactly what I felt back then about being trusted with the winch, but I do remember that I enjoyed being taken out there with him.

Those rigs smelled like crude oil — the same smell that clung to my dad’s overalls when he came home from offshore. That smell, mixed with diesel and salt air, became the scent of my childhood. On location, he was a mix of joking and serious, demanding discipline but also allowing you the freedom to make your own choices and learn from them.

Meals on those trips weren’t exactly five-star dining. A “gourmet spread” usually meant canned pork and beans, saltine crackers, Vienna sausage, or spam. On a good day, I might catch a catfish with the tugboat captain and he would upgrade the menu. Other times, Dad would take me to the Gretna, Louisiana shop, where I helped him prep the tools. Those experiences planted the first seeds of my life in the oilfield.

First Steps Into the Industry

By 1972, I found myself working in the New Orleans shop for a survival craft company. My job was fiberglass repairs on the survival capsules and doing some field service work, including assisting installations and maintenance. My last job was assisting to install survival capsules on the ODECO Ocean Victory.

But the pay — $2.70 an hour — was not enough to live and party on. At 6’1″ and weighing only 135 pounds, I was starving. After nine months, I needed $294 to repair my wrecked motorcycle, so I started looking for other work. Everyone I knew was struggling to make ends meet; I didn’t think too much about what my family or friends thought of me going offshore. A lot of my high school buddies had already chased money to work on the Alaskan pipeline. We were all just looking for a way to get ahead.

Then fortune intervened: the shop accountant left to work in HR for Santa Fe Drilling and gave me a call. He asked if I wanted to make $3.00 an hour on an 84-hour work week — seven days on, seven days off — with all the food I could eat.

I jumped at the chance. I remembered a line from a rock song of the time: “The sign said long haired freaky people need not apply.” So I cut my shoulder-length hair short, knowing I’d never be hired otherwise. I asked my boss to allow me to borrow the company truck to get to the job interview in Houma, Louisiana — but that ended up with me hitchhiking instead. Still, I got the roustabout job and was assigned to the Santa Fe Mariner 2.

“The patch,” through the eyes of a skinny 19-year-old chasing a paycheck, looked like hard, demanding work — but it also paid a lot better than construction jobs on land. I wasn’t afraid of hard work; at 17 years old, weighing 120 pounds, I had spent a summer running an 85-pound jackhammer, busting concrete. Offshore just felt like the next level.

Getting to the Rig

Plans rarely go the way you think. With no money, I borrowed $17 from a friend to take a one-way Greyhound bus from New Orleans to Port Arthur, Texas, where the rig was under construction in the Livingston shipyard.

The bus ride was 19 hours along US 90, since Interstate 10 between New Orleans and Texas wasn’t finished yet. By the time the bus pulled into Port Arthur I was hungry

Hungry and broke, I walked from the bus station to the shipyard. Off in the distance, past the refineries, I saw a derrick rising near a bridge. For a moment I thought it was the huge rig I’d be working on — but as I got closer, I realized the massive structure belonged to the SEDCO 135. In front of it sat my assignment: the much smaller Santa Fe Mariner 2. The Sedco 135 absolutely dwarfed her.

When I arrived at midday, a man stepped out of a small trailer and asked what I was doing. I told him I was there to work. He said everyone was on lunch break and asked for my name and employee number. I asked if I could look around the rig. “Sure,” he said.

It was my first real look at the inner workings of an offshore drilling rig. I felt anxious more than anything else — anxious to get to work, to get that first paycheck, and to stop being hungry.

Life as a Roustabout

When the crew returned from lunch, I was assigned to the crane operator’s crew — all from the same small town in Alabama, making me feel like the odd man out. To make matters worse, I learned I’d only be working four days out of seven and we couldn’t live onboard because the quarters weren’t ready and there was no food supply.

That night, we rode in the back of the crane operator’s pickup truck to a motel. I panicked — I had no money for food or lodging. But the Toolpusher, who I’d met earlier, assigned us rooms. I cleaned up and changed into my spare clothes but skipped dinner when my roommate invited me.

The next morning at the motel diner, everyone ordered breakfast. I sat quietly, stomach growling, as I couldn’t pay. Finally, the crane operator looked at me and said, “Worm, aren’t you going to order anything?” Somewhere along the line, he’d started calling me “Worm,” the usual name for a brand-new oilfield hand. I told him no. He just grinned and said, “Well, Santa Fe is paying for it.”

I don’t remember ever being so relieved. I ordered five pancakes, six eggs, a stack of bacon, and a bowl of grits. After everything I’d been through just to get there, that breakfast tasted great — like the first real meal I’d had in months.

The other hands mostly kept their heads down and worked; I didn’t think much about how they talked or joked, because the pace was busy. At that point, I still thought of the job the way I had at the beginning: a temporary stop to repair my motorcycle, not a lifelong career.

Crew Change and the Hard Lesson

The next three days fell into a rhythm: breakfast, rig work, lunch and dinner, sleep. Then, at midday on crew change, we were told to pack up and return in seven days. I asked about my paycheck — only to be told it would be mailed after my return to the rig.

I had one clean set of clothes, but when I went to change out of my work gear — covered in black cable dope — I discovered my clean clothes had been stolen. With no money and no clean change, I started the long hitchhike back to New Orleans. Cars would slow down, but as soon as the drivers saw me, they sped away. It took two nights before I finally made it back home, mostly thanks to semi-truck drivers who picked me up in the dark.

As I had no paycheck waiting on me, I hitchhiked back to Port Arthur for my next hitch. When I got to the shipyard I saw the Toolpusher and told him I wanted to pull a double hitch. He said if that was the case I would have to do a 3-week hitch and he would see what he could do. He told me yes. I would now have 3 paychecks waiting to be cashed when I got back to New Orleans.

We were now living on the rig and working hard long hours with plenty of overtime as the rig was scheduled to sail out in 2 weeks. This period ended up being one of the most important lessons of my career. Over the next 3 weeks I witnessed 2 workers fall to their deaths. We did not have mandatory personal protective equipment requirements at this time. A few of my workmates had from other jobs suffered amputated fingers and disfigured arms. This I learned was an unfortunate “normal” consequence of working in the drilling and construction industry back then.

Seeing those first offshore deaths made a deep impression on me. I realized I needed to be much more careful, especially working at heights on slippery moving steel. No one really talked about it back then; there were no counseling sessions or debriefs — it was all left to your own thoughts. That was when safety became personal, not just something written on a board. Once we went fully offshore, we started to have weekly safety meetings, most of the focus being on things that needed repair and hazards that had to be addressed.

We towed offshore, and the rig was 270 feet long by 108 feet wide with a towing draft of 10 feet and a drilling draft of 26 feet. The rig pitch and roll motions was 1 to 5 degrees The heave at times matched the wave height. Motions themselves did not bother me, but the number of heavy moving objects did; everything that could move needed to be secured.

The serial number 1 single-piston compensator was designed for a maximum of 20 feet of heave. It leaked compensator fluid all over the derrick and rig decks — a very slippery lubricant. There were lots of slips, trips, and falls. This is when the industry really started to focus on prevention of slips, trips, and falls, and on adding safety guards to rotating equipment to keep fingers and hands safe. I would be remiss not to mention the invention of the non-slip work boot.

During my 40-plus years working on offshore drilling units, I think this was the most important area of focus for accident prevention. Second to this was the development of mental acuity in pre-work safety training programs and personal assessment prior to going to the job site. Another very important area was the training of personnel in management of change. IADC played a significant role in this with the RIG PASS program and similar efforts.

Looking back, I see that the people around me helped shape my approach to safety from the beginning. The crane operator, the Toolpusher, the barge engineer — they were the first ones to teach me tricks of the trade that kept me safe later on. Many of us were new to that specific offshore rig environment, so we leaned on the few persons more experience.

When I finally came back to New Orleans after that 3-week hitch and held three paychecks in my hand, it felt like I had won the lottery in 1973. That was the moment I decided I would continue working on offshore rigs and not walk away after fixing my motorcycle. The high rotation of people being hired, quitting, or getting fired was very large. Many land drillers would come to work only to quit after the first hitch because of the motion — if it was not tied down, it moved. For handling the tubulars, we did not have hydraulic handlers, only mule lines, tuggers, and tag lines.

The high turnover in a relatively new and growing offshore drilling industry provided many advancement opportunities for anyone who had even an ounce of ambition to work hard and learn. On my third hitch, I was promoted to roving roustabout — assistant watchstander Stability Tech — working for the Marine Department. After six months, I was seriously considering joining the U.S. Navy when I was instead promoted to Stability Tech (watchstander). At $4.92 per hour I was making as much as a driller.

After 15 months working in the U.S. Gulf, I was transferred to overseas work. My assignments over the years took me to Trinidad, Malta, Egypt, back to the U.S. Gulf, Brazil, Gabon, Ivory Coast, Equatorial Guinea, Morocco, Malta again, Egypt again, Angola, Nigeria — and many more places that shaped my life and career. Offshore rigs assigned to – Santa Fe Mariner 1, 2, & 3, Blue Water 2, Key Gibraltar, Key Largo, Key Bermuda, Key Hawaii, Key Victoria, Swamp Queen, Swamp Master, Santa Fe Rig 135 over a 20-year period.

In General – People Who Helped Me Advance

The persons who assisted me in my advancement from Roustabout to Senior Regulatory Compliance Manager are too numerous to name, and not having sought their permission, I will refrain from listing them. But to each one, a very special thank you is warranted — whether the feedback on the job came as a pat on the back or a swift boot in the butt to keep me on the correct path.

The MODU Code — the Code for the Construction of Mobile Offshore Drilling Units — was another major thread running through my career. Before the MODU Code, offshore drilling rigs were built to shipping or shore-based standards, with not much added on the industrial side. It became clear that a uniform standard was needed. With industry associations and regulators working together, the 1979 MODU Code was promulgated via the International Maritime Organization. It was later updated in 1989 and then again in 2009.

The 2009 MODU Code was driven in part by IADC — with people like Alan Spackman as key driving forces — along with other industry participants and Flag State regulators at the International Maritime Organization. That revision took approximately five years to complete. It drastically improved the existing Code through broad industry participation and incorporated current and forward-looking, realistic construction standards.

When I look back at my career, my participation in the work of the MODU Code is the accomplishment I am most proud of. I am very thankful to the management of Transocean for allowing me the flexibility and time that had to be dedicated to complete this work — especially given that we were in the middle of a MODU construction boom and many of the new Code requirements were already beginning to be incorporated even before ratification.

From a seven-year-old boy smelling crude oil on his father’s overalls to a Senior Regulatory Compliance Manager helping shape the standards for offshore drilling units worldwide, the oilfield gave me a lifetime of hard lessons, opportunity, and purpose — and I never did look back.

Industry awards:

November 2009, IADC – Recognition of my significant contributions to the Association and its goals, during the development of the IMO Code for the Construction and Equipment of Mobile Offshore Drilling Units, 2009

May 2017 Meritorious Public Service Award –United States Coast Guard – For contribuions while serving as a member of the National Offshore Advisory Committee representing the offshore drilling industry.